[E] Graph Neural Networks

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) is currently the primer approach in applying neural networks to relational data. In this post, we will see the basic formulation and different variations of the GNNs.

- A Brief Introduction to Graphs

- Machine Learning on graphs

- Simple Naive Approach (Adjacency Matrix)

- Graph Neural Networks (Formulation)

- Examples

- Conclusion

- References

A Brief Introduction to Graphs

Graphs are structures that can store complex relations (edges) between objects (nodes). These relations can happen in many shapes. For instance, friendships in the social networks, protein-protein interactions (PPIs), or the user-product interaction as in the recommender systems. We can define all of these problems as a graph and answer lots of questions. For example, what should we recommend to some particular user, what is the role of specific proteins, or which users are fake (bots) in social media?

To make things a little bit more concrete, let’s start by defining the graphs formally and explain some properties related to them.

Graphs are also called networks, but we try to restrict ourselves to use the term graph to prevent the potential confusion between the neural networks.

Graphs \(G = (V, E)\) include set of nodes \((V)\) and set of edges \((E)\). The connection between the nodes is called edges. We can represent the graph as an adjacency matrix \((A)\) where every cell in the matrix is either 0 or 1. If there is a weight between the nodes the adjacency matrix can take arbitrary numbers as well. We can also represent the graphs via the edge list. In this type of representation, we only store the edges between the nodes. Here is an example of a toy graph with only 6 nodes and 7 (undirected) edges.

Adjacency matrix:

| A | B | C | D | E | F | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| B | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| C | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| D | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| E | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| F | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Edge list: [(A, B), (B, C), (B, D), (C, D), (D, E), (D, F), (E, F)]

Graphs can be directed/undirected depending on the problem. For example, the relations on the Facebook social graph are undirected. If you add someone as a friend, you become a friend mutually. On the other side, if you follow someone on Twitter, the relation is directed. It doesn’t apply vice versa.

Apart from being directed/undirected, graphs can also have different types of nodes which we call heterogeneous graphs. For example in the recommender systems, we can represent the users and the items (e.g. movies or products) as separate nodes.

Machine Learning on graphs

There are multiple types of problem formulations in the graph domain that can be solved with supervised/unsupervised settings similar to classical machine learning. Here we will touch upon four of them.

1. Node Classification/Regression

In this type of problem, we aim to solve the node-level tasks such as the detection of fake users (bots) in social media. Bots tend to follow similar patterns in terms of actions (following/posting). We represent the users as nodes in the graph and learn node embeddings based on the graph structure and input features like follower count and post frequency. Then we classify the users based on the node embeddings.

2. Link Prediction

Link prediction is a task to understand the potential relations between the nodes. For instance, in the recommender systems, we can represent the users and the products as nodes in the graph. We can add edges based on the user purchases and define the problem as a link prediction task. At test time, we can make predictions using the learned user and product embeddings and recommend products to users based on the prediction results such as 0/1.

3. Community Detection & Clustering

In community detection & clustering problems, we aim to group similar nodes. For example, in citation graphs, we can represent papers as nodes and create edges between the nodes based on citations. After learning the unsupervised representation of nodes, we can apply any clustering algorithm like KMeans to generate clusters/groups.

4. Graph Classification/Regression

Graph-based tasks are similar to node-level tasks but require making predictions about the full graph instead of just a single node or link. For example, understanding the threads in the Reddit is a discussion-based or not is a binary graph-classification task. Here the nodes are the users, and the links are the replies between them. To make predictions on the graph, it is also essential to incorporate the global structure together with the local features.

After discussing the several problems related to graphs, let’s see how we can apply the neural networks to the graph data.

Simple Naive Approach (Adjacency Matrix)

One basic idea to use the neural networks with the graph-structured data is to use the adjacency matrix as an input. We can flatten the adjacency matrix to be a 1d vector and supply it to the network. The major drawback of this approach is that the adjacency matrix is not permutation invariant. Different ordering of the nodes changes the adjacency matrix and hence the input to the neural network. We will have different outputs for the same graph by just reordering the adjacency matrix. This is not desirable since the input graph is essentially the same. So, one main property that we need to satisfy is the permutation invariance when applying neural networks.

We saw that the adjacency matrix as an input is not sufficient. What can we do? It is time for Graph Neural Networks to come into the stage.

Graph Neural Networks (Formulation)

The motivating idea behind the GNNs is applying the neural networks to the graphs to extract useful features. The fundamental principle is the exchange information between the nodes. This communication is called message passing and, updating the node information with neural networks is called neural message passing.

There are two key components in the GNNs framework:

- Aggregation: Aggregating the information from the neighbors.

- Update: Updating the node information based on the previous information embedding and aggregated message.

Neural Message Passing

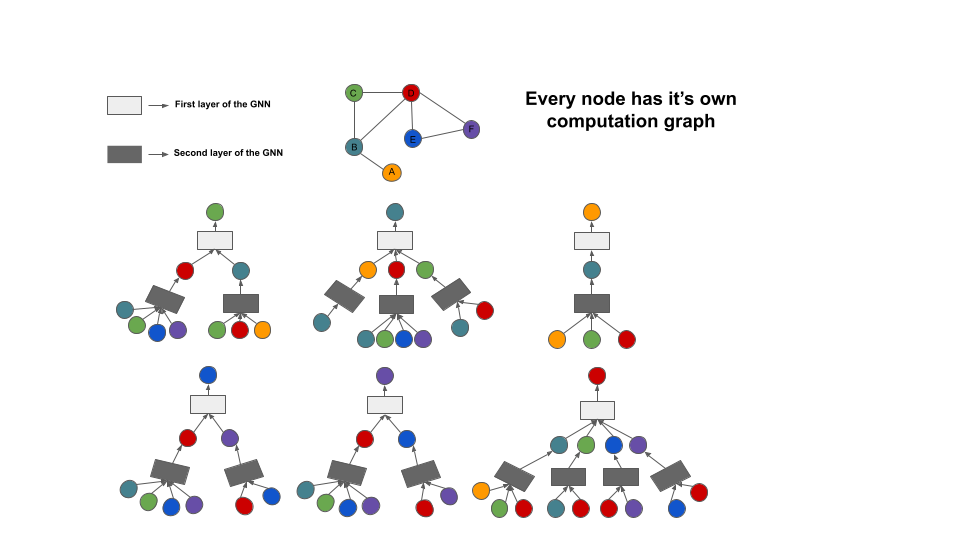

As we stated earlier, neural message passing is the process of exchanging embedding messages between the nodes and updating with the neural networks. Every message passing layer aims to aggregate the neighbor’s information and create a message vector. The principal idea is that every node creates its computation graph and proceed information from its neighborhood. Here is a simple illustration of the process:

In this image, there are two GNN layers that make computations based on the 1-hop neighborhood of its input node. Now lets understand the general idea with some equations and dive into the ocean. Here is the abstract definition of that image: \(\begin{align} h_{u}^{(k+1)} &= UPDATE^{(k)}\bigg(h_{u}^{(k)}, AGGREGATE^{(k)}(\{h_v^{(k)}, \forall{v} \in \mathcal{N}(u)\})\bigg) \\ &= UPDATE^{(k)} \bigg(h_{u}^{(k)}, m_{\mathcal{N}(u)}^{(k)}\bigg) \end{align}\)

In this equation, \(m_{\mathcal{N}(u)}^{(k)}\) is defined as \(m_{\mathcal{N}(u)}^{(k)} = AGGREGATE^{(k)}(\{h_v^{(k)}, \forall{v} \in \mathcal{N}(u)\})\). The aggregation function here can be a non-parametric function such as mean or sum or more complex such as neural networks. To make the computations a bit of concrete, let’s convert them to the equations which we can implement.

\[h_{u}^{(k+1)} = \sigma\bigg(W_{\text{self}}^{(k)}h_{u}^{(k)} + W_{\text{neigh}}^{(k)}\sum_{\substack{v \in \mathcal{N} (u)}}h_v^{(k)} + b^{(k)}\bigg)\]Here \(\sigma\) is an element-wise activation function (e.g. ReLU or Tanh) and \(W_{\text{self}}\) and \(W_{\text{neigh}}\) are learnable parameters. As you might notice, we used the \(\sum\) operator as an aggregation function. If we want to map this equation to our abstract definition:

\(m_{\mathcal{N}(u)} = \sum_{\substack{v \in \mathcal{N} (u)}}h_v\) \(\text{UPDATE}(h_{u}, m_{\mathcal{N}(u)}) = \sigma\bigg(W_{\text{self}}h_{u} + W_{\text{neigh}}m_{\mathcal{N}(u)} + b\bigg)\)

Here we can skip the update operation by adding self-loops to the input graph. In this case, the final equation would be

\[h_{u}^{(k+1)} = \text{AGGREGATE}(\{h_v^{(k)}, \forall_{v} \in \mathcal{N}(u) \cup {\{u\}}\})\]like this. Aggregation functions should satisfy an important property: being permutation invariant. The nodes in the graph have no particular order. The aggregation function should produce always the same result independent from the input order. The mean and the sum function obey this rule. However, we should pay attention when we consider the architectures which have learnable parameters.

It is possible to use the LSTMs as an aggregator function. As you know, LSTMs process the input sequentially. Although having more representational capability brings an advantage, our rule of being “permutation invariant” is unfortunately broken. To overcome this problem, the neighbors of the nodes were given randomly in different orders to the LSTM network. Our goal here is to learn representations independent of the order. Lastly, the final message information is obtained by averaging the outputs.

It is also possible to use attention as another aggregation function. As you might guess, not all the neighbors of a node have equal importance. For example, in citation graphs, some papers may have been cited from much more various articles. They may contain less valuable information when determining the class of a document (as it gets more citations). By applying attention, the importance of the nodes is learned. While any attention mechanism in the literature is possible to use, we will consider the self-attention as in (Veličković et al. 2017). Firstly, we compute the attention between the node \(i\) and \(j\).

\[\begin{equation} e_{ij} = a({\bf W}\vec{h}_i, {\bf W}\vec{h}_j) \end{equation}\]To convert them to probabilities, let’s apply the softmax function:

\[\alpha_{ij} = \mathrm{softmax}_j(e_{ij})=\frac{\exp(e_{ij})}{\sum_{k\in\mathcal{N}_i} \exp(e_{ik})}\]and finally let’s apply a nonlinear activation function:

\[\begin{equation}\label{eqnatt} \vec{h}'_i = \sigma\left(\sum_{j\in\mathcal{N}_i} \alpha_{ij} {\bf W}\vec{h}_j\right). \end{equation}\]The self-attention operation here is applied to the full graph. The authors proposed to inject the graph structure in to the mechanism by performing masked-attention. So, only the attention on edge \(e_{ij}\) considered where \(j\) is in the neighborhood of node \(i\).

Additionally, as in (Vaswani et al. 2017) we can use multi-head attention as well. By applying multiple attention heads independent from each other, we increase the representation power and stabilize the training.

Examples

The complete code example for this blog post can be found in this repository. The code uses pytorch-geometric library. Here we will focus only on some small parts of it and the final output image. We use the Cora dataset as our prediction task. The Cora dataset consists of 2708 scientific publications and includes seven classes. The citation graph consists of 5429 edges. Each publication has a 1433 length feature vector which indicates the absence/presence of particular words from the 1433 length dictionary (bag of words features).

We used Graph Attention Networks (GAT) as our feature extractor. Then we classify the papers with an MLP classifier in an end-to-end manner. Here is the definition of the model class in Pytorch.

class Net(torch.nn.Module):

def __init__(self, dropout_p=0.6):

super(Net, self).__init__()

self.dropout_p = dropout_p

self.conv1 = GATConv(dataset.num_features, 8, heads=8, dropout=dropout_p)

self.conv2 = GATConv(8 * 8, 8, heads=6, concat=True, dropout=dropout_p)

self.classifier = nn.Linear(48, dataset.num_classes)

def extract_features(self, x, edge_index, return_attention_weights=True):

x = F.dropout(x, p=self.dropout_p, training=self.training)

x = F.elu(self.conv1(x, edge_index))

x = F.dropout(x, p=self.dropout_p, training=self.training)

return self.conv2(x, edge_index, return_attention_weights=return_attention_weights)

def forward(self, x, edge_index):

features, _ = self.extract_features(x, edge_index)

x = self.classifier(features)

return F.log_softmax(x, dim=-1)

We define two GATConv and one linear classifier layer. We use six heads with a feature vector of length 8. Before the classification layer, we concatenate these vectors and create the final 48 length feature vector. After the classification layer, we take the log_softmax to convert the logits to log probabilities.

def train(data):

model.train()

optimizer.zero_grad()

out = model(data.x, data.edge_index)

loss = F.nll_loss(out[data.train_mask], data.y[data.train_mask])

loss.backward()

optimizer.step()

def test(data):

model.eval()

out, accs = model(data.x, data.edge_index), []

for _, mask in data('train_mask', 'val_mask', 'test_mask'):

pred = out[mask].max(1)[1]

acc = pred.eq(data.y[mask]).sum().item() / mask.sum().item()

accs.append(acc)

return accs

We define a simple training loop here. An important thing to remember is that we pass the input features (1433 length vector) together with the edge information to the model. GATConv layer handles the message passing state in the background. You can find additional information on that part from this link which describes the message passing procedure in detail.

for epoch in range(1, 101):

train(data)

if epoch % 20 == 0:

train_acc, val_acc, test_acc = test(data)

print(f'Epoch: {epoch:03d}, Train: {train_acc:.4f}, Val: {val_acc:.4f}, '

f'Test: {test_acc:.4f}')

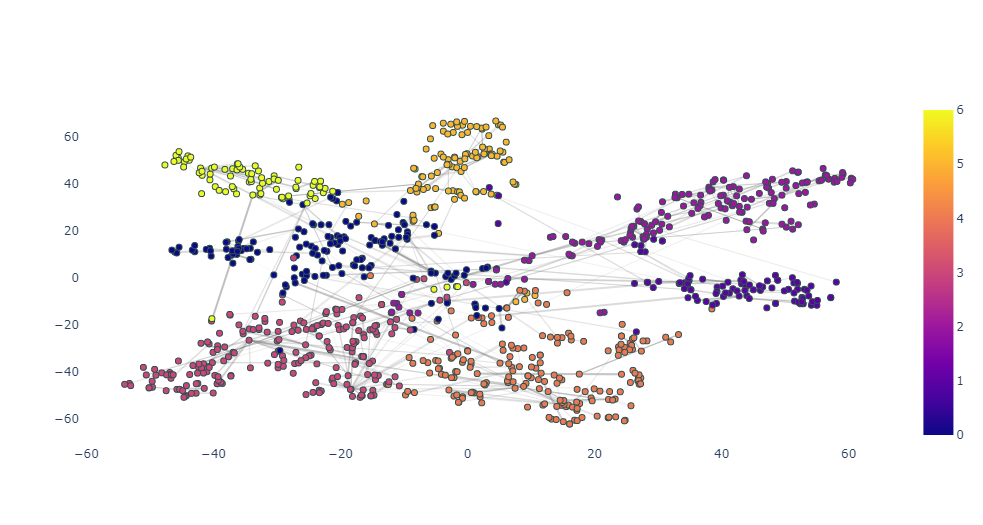

As a final step, we can visualize the learned embeddings for the publications. We apply a TSNE algorithm to 48 dimensional vector and generate the 2d representation of the nodes. Additionally, we plot the edges between the nodes based on the attention weights which indicates the importance of neighborhood nodes while classifying the current node.

Conclusion

In this post, we learned that:

- What the graphs are,

- What kind of problems can be solved with graphs,

- Problem formulations on the graphs from a machine learning perspective,

- Graph Neural Networks and the message passing idea,

- Different message passing procedures

and finally, Graph Attention Networks with some code examples. Andd, that was it :)

Thanks for reading!